Since the introduction of the Building Safety Act, competence is no longer a loose professional expectation. It is a requirement that must be defined, evidenced and sustained. Yet across construction and fire safety, competence is still spoken about in generalities rather than specifics.

Too often, competence is inferred from experience, confidence, or historic practice. People are assumed to be competent because they have “been doing it for years”, because they hold a certificate, or because they appear capable on site. None of these, on their own, meet the standard now expected in a safety-critical environment.

If competence is to be taken seriously, it must be explained properly.

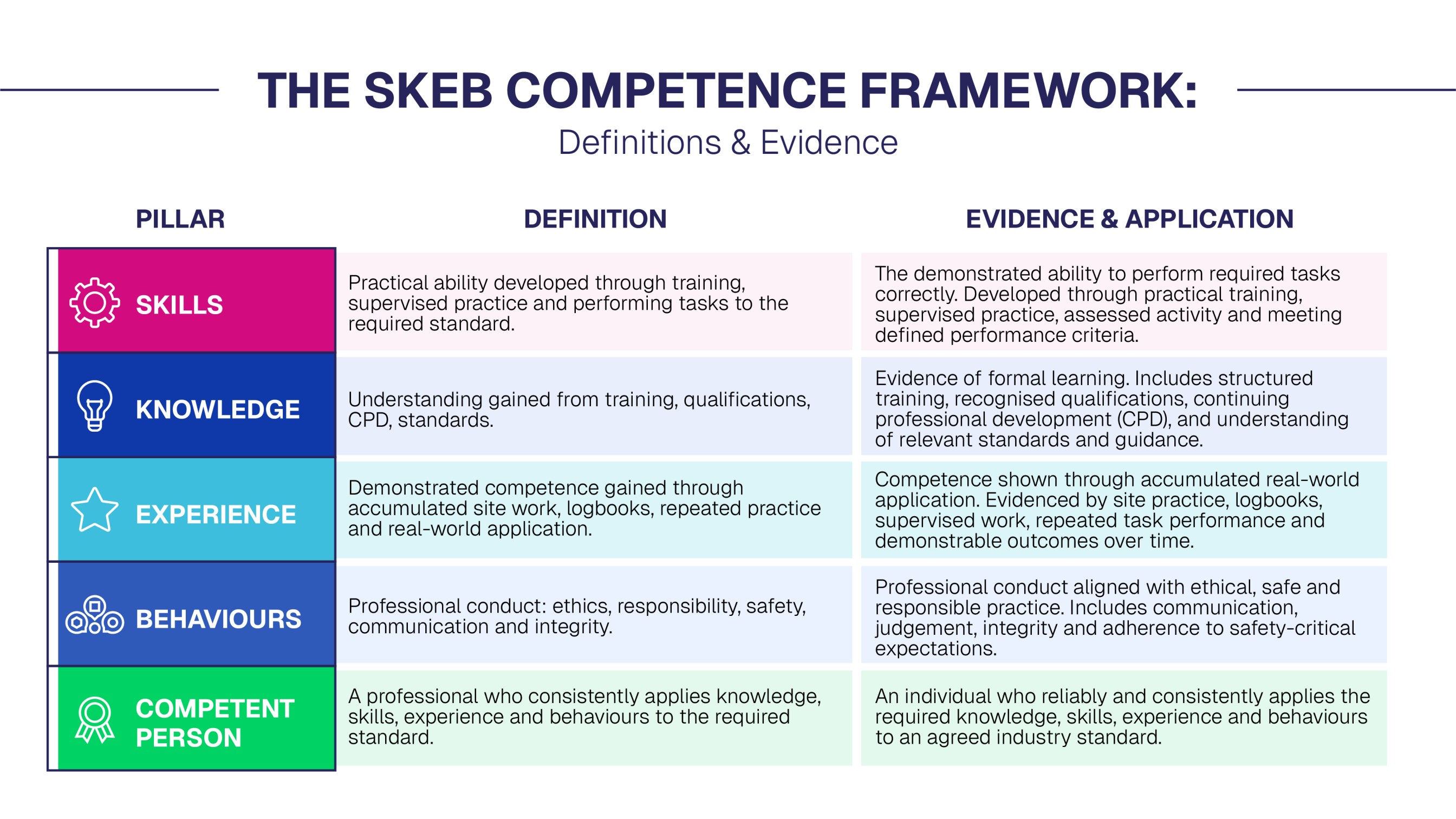

To address this, I have developed the SKEB Competence Pyramid. This is a structured competence model rooted in established educational principles, aligned with SKEB, and designed specifically for safety-critical work such as fire door installation, inspection and maintenance.

It exists to answer a simple question: what does competence actually look like?

Competence Is an Outcome, Not a Label

A competent person is not defined by a single attribute. Competence is not something you claim, inherit, or permanently possess. It is the outcome of several elements working together, in the correct order, and remaining current over time.

The Competence Pyramid is built from five elements:

- Knowledge

- Behaviours

- Skills

- Experience

- Competent Person

The competent person sits at the top of the pyramid because competence is the result of the layers beneath it. If those layers are missing, weak, or outdated, competence cannot be demonstrated.

The Foundations: Knowledge and Behaviours

The most important feature of the Competence Pyramid is that it is not symmetrical. Not all elements carry the same weight.

At the base sit Knowledge and Behaviours. These are the foundations. Everything else depends on them.

Knowledge: The Requirement to Understand

Knowledge is the evidence that a person understands what they are doing and why they are doing it. In educational terms, this is declarative knowledge. It underpins judgement, adaptation and decision-making.

In fire door safety, knowledge includes understanding:

- The purpose of a fire door as a life-safety system

- How fire, smoke and heat behave in buildings

- Why specific tolerances, gaps and materials are specified

- How components interact as a tested system

- The regulatory and legal framework governing the work

Without this understanding, practical actions cannot be justified. A task may be performed neatly, quickly or confidently, but neat execution is not evidence of competence.

A person who cannot explain why they are doing something cannot reliably judge when conditions change, when something is wrong, or when a deviation becomes critical. In safety-critical work, that limitation matters.

This is why knowledge must come first. It governs everything that follows.

Behaviours: The Ethical Dimension of Competence

Alongside knowledge sit Behaviours. Competence is not purely technical. Fire safety work carries moral and professional responsibility.

Behaviours include integrity, accountability, communication and the willingness to prioritise safety over convenience, time pressure or cost. They determine how knowledge and skill are applied in real situations.

A person may understand the requirements and still choose to ignore them. Without the right behaviours, competence is unreliable. This is why behaviours are foundational rather than supplementary.

Knowledge answers what and why. Behaviours determine whether that knowledge is acted on properly.

Skills: Translating Understanding into Action

Once knowledge and behaviours are established, skills can be developed.

Skills represent the ability to perform tasks correctly. They are built through structured training, supervised practice and assessment against defined performance criteria. Skills answer the question how.

In the context of fire doors, this includes the ability to install, inspect or maintain doors in accordance with requirements, using the correct methods, materials and sequences.

However, skills only demonstrate competence when they are informed by knowledge. Practical ability without understanding produces repetition rather than judgement. It works until something changes, then fails.

This distinction is critical. Skill is necessary, but it is not sufficient.

Experience: Demonstrating Consistency Over Time

Experience is where competence moves from isolated performance to reliability.

Experience is not time served. It is competence demonstrated repeatedly in real-world conditions. It is evidenced through site work, logbooks, supervision, repeated task performance and consistent outcomes over time.

Experience refines skills and strengthens judgement, but it does not replace learning. When experience is not accompanied by ongoing knowledge development, it often reinforces outdated or incorrect practice.

This is why experience sits above knowledge and skills, not instead of them.

The Competent Person

At the top of the pyramid sits the competent person.

A competent person is someone who consistently applies the right knowledge, skills, experience and behaviours to the required standard. Consistency is the defining feature.

Competence is not about getting it right occasionally. In a safety-critical environment, it must be reliable, repeatable and defensible.

When the Pyramid Collapses

The Competence Pyramid also shows what happens when one of the foundations is removed.

If knowledge is missing or outdated, the structure fails. Skills and experience may remain, but they are no longer anchored to understanding. What looks like competence becomes habit and muscle memory.

This is not theoretical. The industry sees it regularly. Individuals with years of experience and strong practical ability whose technical knowledge has not kept pace with standards, guidance or regulation.

In the SKEB model, this is not partial competence. It is failed competence.

Without knowledge, the Competence Pyramid collapses.

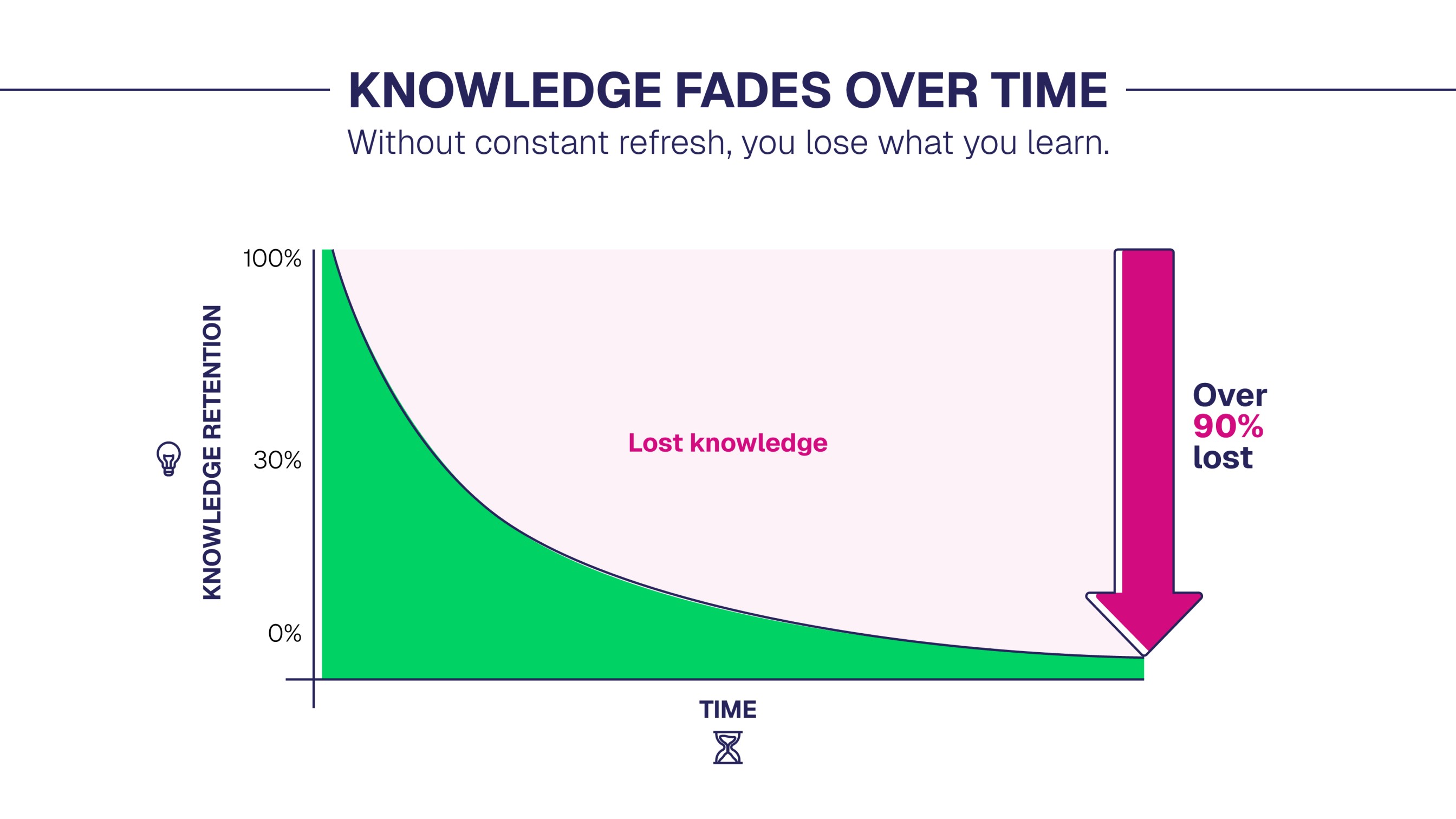

Knowledge Decay and the Forgetting Curve

Recognising knowledge as foundational leads to an uncomfortable reality: knowledge is perishable.

This has been established for well over a century in educational psychology. Beginning with the work of Hermann Ebbinghaus and reinforced by modern cognitive science, research consistently shows that recall and reliability of knowledge decline over time if learning is not revisited, applied, or reinforced. The exact rate of forgetting (commonly referred to as the forgetting curve) varies by individual and context, but the underlying principle is not disputed.

What matters in practice is not that people “forget everything”, but that unused knowledge becomes less accessible and less dependable. Without ongoing retrieval, reinforcement, or real-world application, previously learned information degrades.

For that reason, a qualification or course completed years ago does not, by itself, demonstrate current competence. It may evidence that knowledge once existed, but if that knowledge has not been refreshed, tested, or applied, the foundation of the competence pyramid has eroded, regardless of whether the certificate remains valid.

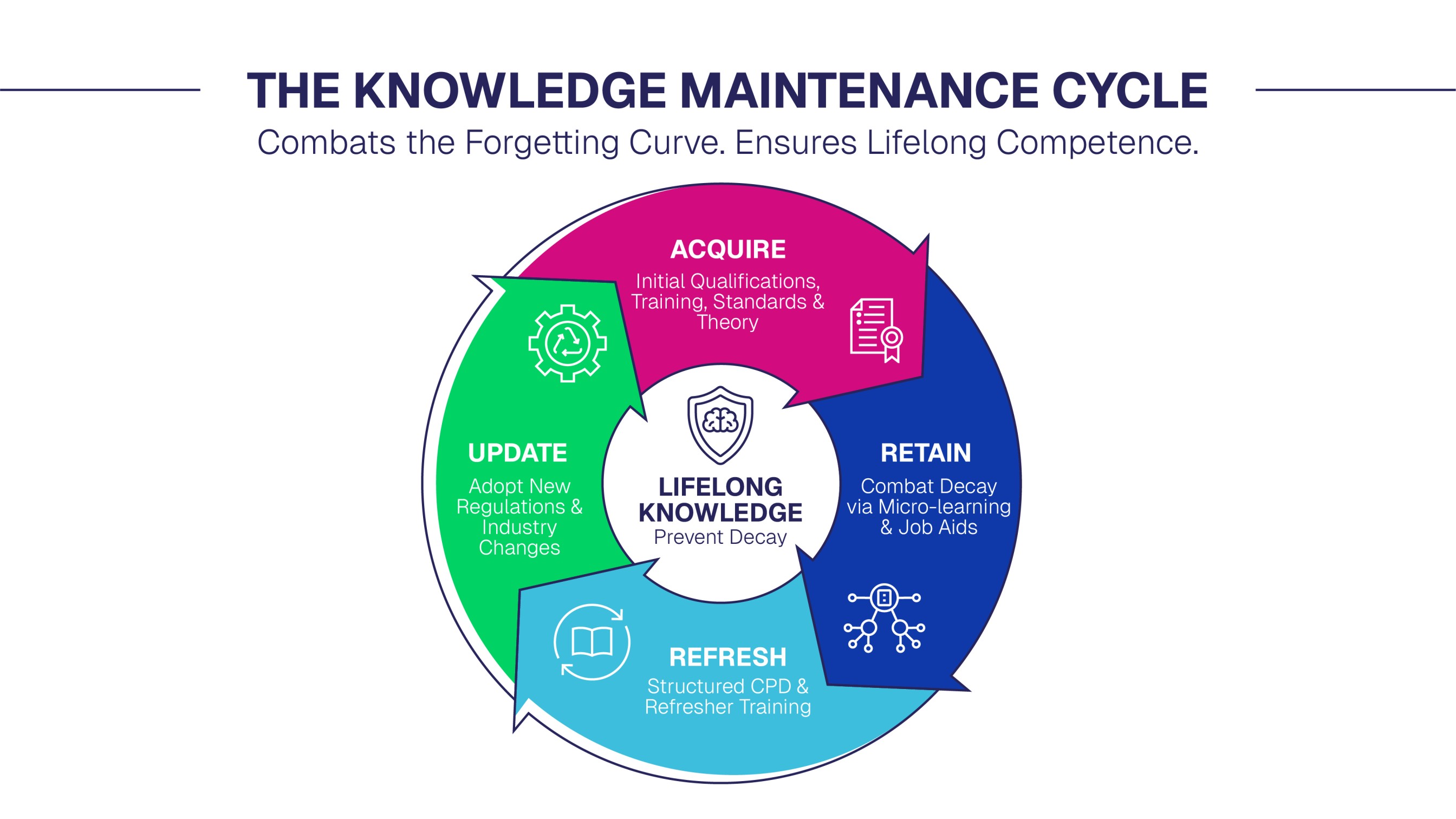

Maintaining Competence: A Lifelong Cycle

Competence is not achieved once. It is maintained.

To counter knowledge decay and the forgetting curve, competence requires a continuous cycle:

- Acquire knowledge through structured training

- Retain it through reinforcement, micro-learning and job aids

- Refresh it through structured CPD and refresher training

- Update it as standards, guidance and regulation evolve

This is how competence is sustained over a career. Without this cycle, knowledge fades, judgement weakens and competence can no longer be relied upon.

What Competence Looks Like in Practice

Competence is not a badge, a scheme, or a one-off course. It is a structure that can be examined and tested.

The SKEB Competence Pyramid provides a clear way to define competence, evidence it, and maintain it over time. It sets out what must be present, what order matters, and why ongoing learning is not optional in safety-critical work.

If the foundations are solid and maintained, competence stands. If they are not, it does not.

In an industry responsible for life safety, that distinction is not academic. It is fundamental.

About the Author and UK Fire Door Training

This framework is the product of a background that sits at a relatively unusual intersection in the fire door industry.

I am Jonny Millard, Managing Director of UK Fire Door Training, and a former secondary school teacher. Before entering the fire safety sector, I worked in education, developing a practical understanding of pedagogy, learning theory, assessment and how people actually acquire, retain and apply knowledge over time.

That background places me in a unique position within the fire door industry. There are very few people working in this space with a formal understanding of how learning works, how competence develops, and why knowledge decays if it is not actively maintained.

After leaving teaching, I became a fire door inspector and worked directly with fire doors in the built environment. What became immediately clear was that many of the issues labelled as “poor workmanship” or “lack of competence” were, in reality, failures of education. People were being asked to perform safety-critical tasks without a sufficient understanding of the underlying principles, and without any structured approach to maintaining that knowledge over time.

UK Fire Door Training was established in response to that problem.

The organisation was set up with a clear aim: to raise the standard of learning and competence building in the fire door industry, not just through training delivery, but through better educational design, clearer competence frameworks and a stronger link between knowledge, skills, experience and behaviour.

Today, UK Fire Door Training is the UK’s largest dedicated fire door training provider. We deliver structured theoretical learning, practical training, assessment and ongoing CPD to thousands of learners each year, from individual installers and inspectors to large organisations responsible for fire safety across complex building portfolios.

The SKEB Competence Pyramid and the associated knowledge maintenance cycle reflect this combined perspective. They are informed both by educational theory and by real-world fire door inspection and training practice. They exist to provide the industry with a clearer, more defensible way to define, evidence and maintain competence in a safety-critical discipline.

This is not a theoretical exercise. It is the result of applying pedagogy to fire safety, with the explicit aim of improving outcomes, reducing risk and raising standards across the industry.

hello Jonny, you are 100% correct.

We will be participating on your programs beginning of new year. is a must.

please continue sending the training programs.

our wishes for good holidays and prosperous new year.